The History of the World Professional Armwrestling Association (WPAA)

Steve Simons

Steve Simons

In the early '70s, Steve Simons, an investment banker, caught the World Wristwrestling Championship on ABC's Wide World of Sports. He was so captivated by what he saw on television that he travelled to the WWC National Championships in Las Vegas in May 1974 and offered to buy the company from Bill Soberanes and Dave Devoto. Steve felt that he could improve armwrestling and make it grow by doing things such as offering monetary rewards to the winners, tidying up the rules, and running tournaments in different parts of the country. To his regret, Bill and Dave weren’t interested in selling. Undeterred, Steve decided that with his background in sports and entertainment, he had the ability to form a company and run an armwrestling tournament circuit himself. To get things off on the right foot, he partnered with Marvin Cohen, a college friend and armwrestler with experience in the sport, to form the World Professional Armwrestling Association (WPAA) in late spring of 1974.

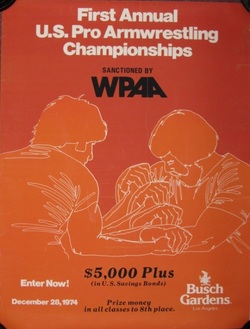

Steve wanted to make a splash with his inaugural event. In mid-1974 he went to meet with executives at Busch Gardens, an amusement park in Van Nuys, Los Angeles. His pitch was that he was forming a new armwrestling organization and he wanted to run a national championship at the park in return for a couple thousand dollars to cover costs. The park would benefit from extra people who would visit the park because of the tournament. Park management agreed and the inaugural WPAA U.S. Pro Armwrestling Championships would be held on December 28th, 1974.

Steve wanted to make a splash with his inaugural event. In mid-1974 he went to meet with executives at Busch Gardens, an amusement park in Van Nuys, Los Angeles. His pitch was that he was forming a new armwrestling organization and he wanted to run a national championship at the park in return for a couple thousand dollars to cover costs. The park would benefit from extra people who would visit the park because of the tournament. Park management agreed and the inaugural WPAA U.S. Pro Armwrestling Championships would be held on December 28th, 1974.

A few weeks after his meeting at Busch Gardens, Steve’s friend David Mirisch gave the WPAA a big boost. David was a Beverly Hills publicist and Steve was a partner in David Mirisch Enterprises. David had a number of connections in the entertainment industry, and he was able to put Steve in contact with executives at CBS Sports. Steve, in his twenties at the time, went to the CBS meeting with pictures of everyday people in hand. He talked about how armwrestling was a sport in which people from all walks of life could compete and that if presented well, could really connect with spectators. He also talked about the Petaluma World Wristwrestling Championships (WWC) and said he could do better. CBS agreed to take a risk and made a deal with the WPAA paying the organization $10,000 for television rights to the 1974 National Championships.

With a great venue and national television coverage secured, Steve was able to get a variety of national sponsors for the event, and was able to do considerable promotion. The WWC was not thrilled by the idea of another organization holding a televised National Championship, and mailed a letter to past Petaluma winners informing them that they would be banned from competing in the World Wristwrestling Championships if they competed in the WPAA tournament. Few competitors heeded this warning and those who wanted to go to the WPAA event went anyway. In the end, competitors were not banned from Petaluma, probably because it would have meant diminishing the quality of the championships if the top competitors were not present.

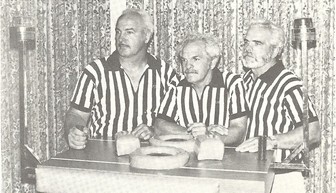

On the day of the event, Los Angeles experienced particularly poor weather, with heavy winds and approximately three inches of rain. However, armwrestlers who braved the weather were impressed with the venue and professionalism of the event. This was the first American tournament to offer cash prizes, and therefore was recognized by many as the first “pro” event -- $750 was up for grabs for first in the heavyweight class, and $500 for first in the other classes. Money was being paid down to eighth place. Four right handed classes were offered for the men, and there was a single open right hand class for the women. Classes were single elimination, but seeded so that competitors who were expected to get far in the tournament were kept separate in early rounds. (While studying at Illinois University, Steve was captain of the tennis team, and he felt single elimination, seeded events were the way to go for speed and entertainment value.) Steve enlisted the Jeffrey Brothers – three brothers who formed the first company that manufactured professional armwrestling tables – to provide the competition table, which was a stand-up pegged table with pin pads and elbows slots.

With a great venue and national television coverage secured, Steve was able to get a variety of national sponsors for the event, and was able to do considerable promotion. The WWC was not thrilled by the idea of another organization holding a televised National Championship, and mailed a letter to past Petaluma winners informing them that they would be banned from competing in the World Wristwrestling Championships if they competed in the WPAA tournament. Few competitors heeded this warning and those who wanted to go to the WPAA event went anyway. In the end, competitors were not banned from Petaluma, probably because it would have meant diminishing the quality of the championships if the top competitors were not present.

On the day of the event, Los Angeles experienced particularly poor weather, with heavy winds and approximately three inches of rain. However, armwrestlers who braved the weather were impressed with the venue and professionalism of the event. This was the first American tournament to offer cash prizes, and therefore was recognized by many as the first “pro” event -- $750 was up for grabs for first in the heavyweight class, and $500 for first in the other classes. Money was being paid down to eighth place. Four right handed classes were offered for the men, and there was a single open right hand class for the women. Classes were single elimination, but seeded so that competitors who were expected to get far in the tournament were kept separate in early rounds. (While studying at Illinois University, Steve was captain of the tennis team, and he felt single elimination, seeded events were the way to go for speed and entertainment value.) Steve enlisted the Jeffrey Brothers – three brothers who formed the first company that manufactured professional armwrestling tables – to provide the competition table, which was a stand-up pegged table with pin pads and elbows slots.

The 1974 WPAA U.S. Pro Armwrestling Championships were considered a success by those involved and gave them optimism about the sport’s future. It was the biggest armwrestling event ever held up to that point in time. Unfortunately, about a week later, Steve received a call with bad news from Frank Chirkinian, a producer from CBS Sports. Frank explained that CBS would not be airing the event. There were a few reasons given. The tournament was held in an outside venue. Although there was a canopy cover to provide shade and protection against rain, the sides of the arena were open and wind and rain blew in and created a lot of noise. The poor weather also meant that there were fewer park visitors than usual, and consequently the event didn't benefit from a large crowd. Also, because this was CBS' first time filming such an event, they didn't feel like they filmed everything the way they should have. They decided to consider it a "learning experience" upon which they could build in the future. This was a huge blow to Steve, as he was counting on the coverage to support all of his other plans.

Steve persevered and decided to use the money he received from CBS to focus on developing the organization. He knew that he wanted to hold a series of regional events leading up to a year-end National Championship, so in 1975 the WPAA tested this formula on a limited scale. A handful of regional tournaments were held on the west coast that year. The events offered approximately $200 to the first place winners of these events, and they attracted a decent number of competitors. The first of these regional tournaments also featured a new Jeffrey Brothers table that had round, padded, doughnut-style elbow cups. These elbow cups became the standard ones used for WPAA events.

Both Marvin and Steve were involved in running the first WPAA tournaments, but it within a few months they started to have differences of opinion as to the direction the WPAA should take. Before long Marvin asked Steve to buy him out, and Steve obliged. Marvin would return to promoting a few years later and be credited for putting together the biggest pro armwrestling tournament of all time -- the Over the Top World Championships.

In mid 1975, Steve had the good fortune of someone coming up with the idea to hold armwrestling matches between football players to be aired during NFL game half-times. CBS, having already developed a relationship with Steve, contacted him to ask if he would be interested in running these matches. Steve jumped at the chance and these matches were sanctioned by the WPAA. These matches helped raise public awareness of armwrestling, and gave the WPAA publicity. (For a detailed article about the 1975 NFLPA Armwrestling Championship, click here)

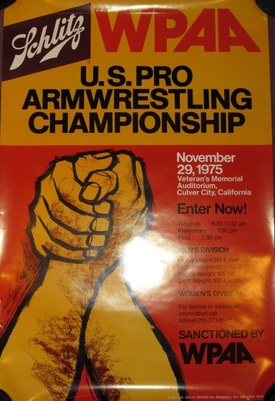

The 1975 U.S Pro Armwrestling Championship was held in Culver City, a city in western Los Angeles County, California. John Woolsey successfully defended his heavyweight title. First place winners received $500, a trophy, and an engraved watch worth approximately $200. These would remain standard prizes for the year-end championships for approximately the next ten years.

Steve persevered and decided to use the money he received from CBS to focus on developing the organization. He knew that he wanted to hold a series of regional events leading up to a year-end National Championship, so in 1975 the WPAA tested this formula on a limited scale. A handful of regional tournaments were held on the west coast that year. The events offered approximately $200 to the first place winners of these events, and they attracted a decent number of competitors. The first of these regional tournaments also featured a new Jeffrey Brothers table that had round, padded, doughnut-style elbow cups. These elbow cups became the standard ones used for WPAA events.

Both Marvin and Steve were involved in running the first WPAA tournaments, but it within a few months they started to have differences of opinion as to the direction the WPAA should take. Before long Marvin asked Steve to buy him out, and Steve obliged. Marvin would return to promoting a few years later and be credited for putting together the biggest pro armwrestling tournament of all time -- the Over the Top World Championships.

In mid 1975, Steve had the good fortune of someone coming up with the idea to hold armwrestling matches between football players to be aired during NFL game half-times. CBS, having already developed a relationship with Steve, contacted him to ask if he would be interested in running these matches. Steve jumped at the chance and these matches were sanctioned by the WPAA. These matches helped raise public awareness of armwrestling, and gave the WPAA publicity. (For a detailed article about the 1975 NFLPA Armwrestling Championship, click here)

The 1975 U.S Pro Armwrestling Championship was held in Culver City, a city in western Los Angeles County, California. John Woolsey successfully defended his heavyweight title. First place winners received $500, a trophy, and an engraved watch worth approximately $200. These would remain standard prizes for the year-end championships for approximately the next ten years.

Having considered the 1975 events to have been successful, for 1976 the WPAA decided to significantly expand their operations. They set out to organize approximately a dozen regional tournaments all over the country. These tournaments would be dubbed part of the Grand Prix of Armwrestling circuit. The first place winners of these events would win $100 and the top four finishers in each class would qualify to attend the year-end championships.

Based on the success of the WPAA’s first few events, Steve was able to negotiate deals with several amusement parks across the United States to host the regional tournaments. Steve’s skill in promotions, combined with quality venues, cash prizes, and World Championship qualifying opportunities, generated substantial interest in the events.

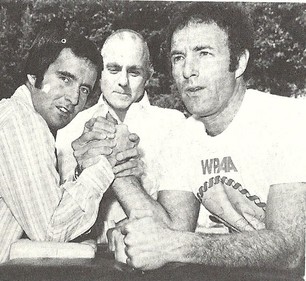

Steve thought of innovative ways to bring attention to WPAA event. Through his involvement in David Mirisch Enterprises, Steve had developed connections with several celebrities. He decided to invite entertainers such as actor James Caan, and singers Trini Lopez and Pat Boone to sit on the WPAA Board of Directors. The Board of Directors was simply for show, and a good way to attract publicity. Apparently the board members got a kick out of watching the armwrestling tournaments.

Based on the success of the WPAA’s first few events, Steve was able to negotiate deals with several amusement parks across the United States to host the regional tournaments. Steve’s skill in promotions, combined with quality venues, cash prizes, and World Championship qualifying opportunities, generated substantial interest in the events.

Steve thought of innovative ways to bring attention to WPAA event. Through his involvement in David Mirisch Enterprises, Steve had developed connections with several celebrities. He decided to invite entertainers such as actor James Caan, and singers Trini Lopez and Pat Boone to sit on the WPAA Board of Directors. The Board of Directors was simply for show, and a good way to attract publicity. Apparently the board members got a kick out of watching the armwrestling tournaments.

Steve also came across a great idea while watching a few minutes of the Jerry Lewis Telethon for MDA Telethon, during which he saw STP (the motor oil company) donate $100,000 to the Muscular Dystrophy Association. The idea came to him in a flash: he contacted STP and convinced them to give just a portion of this amount to the WPAA. In return, STP would be recognized as event sponsors and increase exposure in major markets across the United States, plus they would get national television exposure. Also, WPAA would donate a portion of its profits (approximately the same amount as the sponsorship) to the Muscular Dystrophy Association. By linking WPAA events to a reputable charity, Steve increased his chances of obtaining more sponsorships and media coverage. The WPAA soon adopted the slogan “Strong Arms Compete so Weak Legs Can Walk”.

The WPAA made most of its money through appearance fees paid by amusement parks, as well as through TV deals. A portion of the entry fees went to the park, while the remainder, as well as the profit from WPAA t-shirt and souvenir sales was donated to charity. This formula was used for most of the WPAA’s existence.

In every city he visited, Steve arranged for media attention, be it radio, newspaper, television or any combination of the three. The angle he always pitched was that armwrestling was a sport in which people from all walks of life competed. It was a sport that almost everyone has tried at some point and that anyone can do. Armwrestling was an opportunity for people who were athletic, but perhaps not good enough to compete in traditional sports on a professional level, to have a chance at a moment in the spotlight. Steve always made a point to talk about the different professions of those who competed in armwrestling. He really tried to promote it as an “everyman” sport.

When asked about why he got into the promotion of armwrestling tournaments, Steve liked to joke that he always wanted to own a pro sports franchise, but could not afford to buy the LA Rams. The alternative was to start his own sport. He liked armwrestling and wanted to give it the dignity it deserved by taking it out of the barrooms. He liked to say that his events were the result of “champagne taste and a coca-cola budget”. He also coined the phrase “armwrestling is 40% strength, 40% technique, and 20% guts (who wants it more)”.

After a few years of growth, in 1977 Steve was able to negotiate another contract with CBS Sports for them to film the 1977 and 1978 year-end championships, which by this point were called the WPAA "World" Championships, and air the event on CBS Sports Spectacular. After a three year break, WPAA's biggest tournament would once again be broadcast on national television. Steve obtained $25,000 for the rights to film and broadcast these events.

Steve was also fortunate to score another major deal around this time. Up to that point, the majority of events were held in amusement parks. This meant that during the winter months not as many tournaments could be scheduled because of the poor weather. A call from Buck Sassenfield, a man who represented shopping malls around the country, changed this. He was interested in running armwrestling events in mall centre courts year-round. The decision was a no-brainer for Steve and he jumped at the opportunity. Malls were a natural fit for armwrestling tournaments. In amusement parks there were many other distractions (rides, games), but in malls the armwrestling tournaments would be the big show. Steve went on to run dozens of tournaments in malls over the next three to four years.

1978 also marked the year of the WPAA’s expansion into international markets: Canada and Great Britain. Steve put on the WPAA Canadian Armwrestling Championships for 10 to 12 years in a row (usually in Toronto) and the WPAA British Armwrestling Championships for several years as well (usually in London). In Canada the events aired on CTV Wide World of Sports, and in Great Britain the events aired on ITV World of Sports.

Within a couple of years, the WPAA was operating like a well oiled machine. Every time Steve successfully ran a tournament in an amusement park the word spread and it became easier for him to secure other venues. A few weeks prior to each event, Steve would send Joe Petrovich, the WPAA’s advance man, to iron out the logistics with the park. The weekend of the event, Steve would arrive by plane on the Friday morning with a collapsible Jeffrey Brothers armwrestling table in tow. He would make the rounds with the different media to promote the event. On the Saturday, he would oversee the tournament, and act as emcee. Once the event was done, he’d wrap everything up and fly back home and resume his day job as a talent agent in Beverly Hills.

The WPAA made most of its money through appearance fees paid by amusement parks, as well as through TV deals. A portion of the entry fees went to the park, while the remainder, as well as the profit from WPAA t-shirt and souvenir sales was donated to charity. This formula was used for most of the WPAA’s existence.

In every city he visited, Steve arranged for media attention, be it radio, newspaper, television or any combination of the three. The angle he always pitched was that armwrestling was a sport in which people from all walks of life competed. It was a sport that almost everyone has tried at some point and that anyone can do. Armwrestling was an opportunity for people who were athletic, but perhaps not good enough to compete in traditional sports on a professional level, to have a chance at a moment in the spotlight. Steve always made a point to talk about the different professions of those who competed in armwrestling. He really tried to promote it as an “everyman” sport.

When asked about why he got into the promotion of armwrestling tournaments, Steve liked to joke that he always wanted to own a pro sports franchise, but could not afford to buy the LA Rams. The alternative was to start his own sport. He liked armwrestling and wanted to give it the dignity it deserved by taking it out of the barrooms. He liked to say that his events were the result of “champagne taste and a coca-cola budget”. He also coined the phrase “armwrestling is 40% strength, 40% technique, and 20% guts (who wants it more)”.

After a few years of growth, in 1977 Steve was able to negotiate another contract with CBS Sports for them to film the 1977 and 1978 year-end championships, which by this point were called the WPAA "World" Championships, and air the event on CBS Sports Spectacular. After a three year break, WPAA's biggest tournament would once again be broadcast on national television. Steve obtained $25,000 for the rights to film and broadcast these events.

Steve was also fortunate to score another major deal around this time. Up to that point, the majority of events were held in amusement parks. This meant that during the winter months not as many tournaments could be scheduled because of the poor weather. A call from Buck Sassenfield, a man who represented shopping malls around the country, changed this. He was interested in running armwrestling events in mall centre courts year-round. The decision was a no-brainer for Steve and he jumped at the opportunity. Malls were a natural fit for armwrestling tournaments. In amusement parks there were many other distractions (rides, games), but in malls the armwrestling tournaments would be the big show. Steve went on to run dozens of tournaments in malls over the next three to four years.

1978 also marked the year of the WPAA’s expansion into international markets: Canada and Great Britain. Steve put on the WPAA Canadian Armwrestling Championships for 10 to 12 years in a row (usually in Toronto) and the WPAA British Armwrestling Championships for several years as well (usually in London). In Canada the events aired on CTV Wide World of Sports, and in Great Britain the events aired on ITV World of Sports.

Within a couple of years, the WPAA was operating like a well oiled machine. Every time Steve successfully ran a tournament in an amusement park the word spread and it became easier for him to secure other venues. A few weeks prior to each event, Steve would send Joe Petrovich, the WPAA’s advance man, to iron out the logistics with the park. The weekend of the event, Steve would arrive by plane on the Friday morning with a collapsible Jeffrey Brothers armwrestling table in tow. He would make the rounds with the different media to promote the event. On the Saturday, he would oversee the tournament, and act as emcee. Once the event was done, he’d wrap everything up and fly back home and resume his day job as a talent agent in Beverly Hills.

The WPAA Grand Prix Circuit increased in size every year during the ‘70s. The 1976 series included stops in approximately a dozen cities, the 1977 series included 18 cities, and the 1978 series included stops in 21 cities plus the Canadian and British Championships. The cash prizes at regional events was gradually reduced and finally eliminated by 1978, but this had little effect on attendance – many competitors still wanted to try to qualify for the World Championships where they could have a shot at the bigger prizes and possible TV exposure.

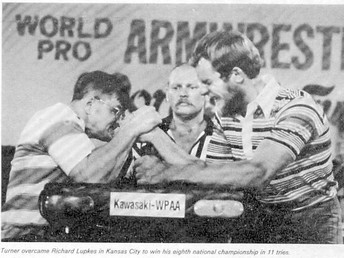

The 1977 WPAA World Championships was the first WPAA Worlds to be held outside of California. Since WPAA tournaments were being held across the country, Steve felt it made sense to hold the year-end event in a more central location which would increase accessibility. In 1977 the event would be held in Houston, Texas, before moving on to Kansas City, Missouri, for a four-year stint. (A similar logic would be used years later for ArmTV’s ROTN Championships.) Throughout the ‘80s, the majority of WPAA World Championships were located in central states.

By the end of the ‘70s, WPAA tournaments had been held in 42 different states (including Hawaii), plus the Virgin Islands. Within the first five years of the WPAA’s existence, virtually all of the top armwrestlers of the era had Steve Simons’ events. John Woolsey, Virgil Arciero, Al Turner, Clay Rosencrans, and Johnny Walker all regularly competed in WPAA tournaments, making the World Championships a very prestigious tournament.

In 1979 Steve opted to enlist the services of Mizlou, a syndicator of sports television, to take care of the filming production of the World Championships, rather than arrange a deal with CBS. This gave the WPAA the freedom to shop the show around to different networks. Through Mizlou, the WPAA World Championships were able to get on Canadian and British airwaves. Pleased with his experience with Mizlou, the company stayed on and produced all of the subsequent WPAA World Championships.

The 1977 WPAA World Championships was the first WPAA Worlds to be held outside of California. Since WPAA tournaments were being held across the country, Steve felt it made sense to hold the year-end event in a more central location which would increase accessibility. In 1977 the event would be held in Houston, Texas, before moving on to Kansas City, Missouri, for a four-year stint. (A similar logic would be used years later for ArmTV’s ROTN Championships.) Throughout the ‘80s, the majority of WPAA World Championships were located in central states.

By the end of the ‘70s, WPAA tournaments had been held in 42 different states (including Hawaii), plus the Virgin Islands. Within the first five years of the WPAA’s existence, virtually all of the top armwrestlers of the era had Steve Simons’ events. John Woolsey, Virgil Arciero, Al Turner, Clay Rosencrans, and Johnny Walker all regularly competed in WPAA tournaments, making the World Championships a very prestigious tournament.

In 1979 Steve opted to enlist the services of Mizlou, a syndicator of sports television, to take care of the filming production of the World Championships, rather than arrange a deal with CBS. This gave the WPAA the freedom to shop the show around to different networks. Through Mizlou, the WPAA World Championships were able to get on Canadian and British airwaves. Pleased with his experience with Mizlou, the company stayed on and produced all of the subsequent WPAA World Championships.

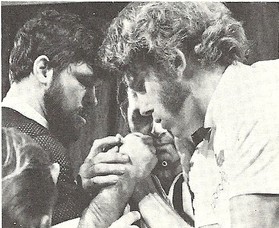

Over the years, the WPAA experimented with different rules, bracket systems, and tables. A significant rule change came about at the start of the 1978 season – the addition of the 4 count rule (two go start). After filming the 1977 World Championships, CBS felt that many of the matches were over too fast. To help fix this, a new rule was implemented where during the first four seconds of the match, only the competitors arms could move. Between the first and second "go" commands, the shoulders had to remain still. A competitor could win the match within these four seconds if he you could pin his opponent just using his arm. Otherwise, the competitors had to wait for the second “go” and then could move their bodies as usual. The command was “ready – go…….go”. This rule change had many detractors, however it remained a staple of WPAA events.

Another rule was added around 1980 whereby competitors whose grips slipped apart while in a neutral position two times in a row were then started in a “powerlock”, a position where competitors wrists are somewhat curled into each other. (Steve was not a fan of using straps to keep competitors hands together. He saw them as a liability because they limited movement. If a competitor was injured because of them, Steve was worried that the WPAA could be sued.) Once in this position, any competitor that turned out of it or caused a slip to occur would lose the match. This rule led to additional problems, as it is not always clear who causes the slip and the referee is then looked upon to determine the winner.

The tournament format that the WPAA used changed a few times over the years, and was often flexible and tailored to the number of entries. One feature that never changed was that the events were always seeded. If the competitors were known to the tournament organizers, the top armwrestlers were kept on opposite ends of the bracket, so that they wouldn’t meet until late in the event. The World Championships were always single elimination (either until the field was withered down to the top eight competitors in each class, or all the way through until the end). Regional tournaments would generally use some form of double elimination, but round robins could occur when the number of entries was low. The single elimination World Championships discouraged some pullers from attending, although because of the TV coverage, the events still had considerable draw.

The ‘70s saw a number of innovations to the armwrestling tables used by the WPAA. To meet Steve’s travel requirements, the Jeffrey Brothers developed the first collapsible armwrestling table, which could be easily wheeled around. In 1975, they also introduced an electronic table with flashing lights that would go off when a pin was detected. However, there would often be problems with the lights going on at wrong time. The technology was improved and these tables were used sporadically at WPAA events over the next couple of years. Nevertheless, there were still occasional problems, and many people felt the lights had too much of a carnival feel, so these tables fell out of use completely around 1978.

Another rule was added around 1980 whereby competitors whose grips slipped apart while in a neutral position two times in a row were then started in a “powerlock”, a position where competitors wrists are somewhat curled into each other. (Steve was not a fan of using straps to keep competitors hands together. He saw them as a liability because they limited movement. If a competitor was injured because of them, Steve was worried that the WPAA could be sued.) Once in this position, any competitor that turned out of it or caused a slip to occur would lose the match. This rule led to additional problems, as it is not always clear who causes the slip and the referee is then looked upon to determine the winner.

The tournament format that the WPAA used changed a few times over the years, and was often flexible and tailored to the number of entries. One feature that never changed was that the events were always seeded. If the competitors were known to the tournament organizers, the top armwrestlers were kept on opposite ends of the bracket, so that they wouldn’t meet until late in the event. The World Championships were always single elimination (either until the field was withered down to the top eight competitors in each class, or all the way through until the end). Regional tournaments would generally use some form of double elimination, but round robins could occur when the number of entries was low. The single elimination World Championships discouraged some pullers from attending, although because of the TV coverage, the events still had considerable draw.

The ‘70s saw a number of innovations to the armwrestling tables used by the WPAA. To meet Steve’s travel requirements, the Jeffrey Brothers developed the first collapsible armwrestling table, which could be easily wheeled around. In 1975, they also introduced an electronic table with flashing lights that would go off when a pin was detected. However, there would often be problems with the lights going on at wrong time. The technology was improved and these tables were used sporadically at WPAA events over the next couple of years. Nevertheless, there were still occasional problems, and many people felt the lights had too much of a carnival feel, so these tables fell out of use completely around 1978.

Tables with straight across elbow pads are associated with the WPAA, but the organization did in fact experiment with offset elbow pads for a brief time in the ‘70s. Virgil Arciero, one of the top super heavyweight competitors of the era, felt they were better and safer based on experimenting he had done. However, after a few broken arms in WPAA competitions, Steve decided to switch back to straight across pads. The debate between which types of tables lead to more broken arms, those with straight across elbow pads or those with offset elbow pads, continues to this day.

Beer companies were major sponsors of the WPAA for several years. Budweiser and the Schlitz Brewing Company sponsored the first WPAA events in the mid-70s. A little later, Steve managed to secure sponsorship from Miller and Carling O’Keefe. When Steve travelled to Milwaukee to meet with representatives of the Miller Brewing Company, he proceeded to tell them that sponsoring WPAA armwrestling tournaments was a great way to reach their target market. Miller signage could feature prominently at all events, on all event t-shirts, as well as in the television production of the World Championships. Miller agreed and Miller High Life became the WPAA’s biggest sponsor in the early ‘80s.

Beer companies were major sponsors of the WPAA for several years. Budweiser and the Schlitz Brewing Company sponsored the first WPAA events in the mid-70s. A little later, Steve managed to secure sponsorship from Miller and Carling O’Keefe. When Steve travelled to Milwaukee to meet with representatives of the Miller Brewing Company, he proceeded to tell them that sponsoring WPAA armwrestling tournaments was a great way to reach their target market. Miller signage could feature prominently at all events, on all event t-shirts, as well as in the television production of the World Championships. Miller agreed and Miller High Life became the WPAA’s biggest sponsor in the early ‘80s.

Up until 1982, Steve Simons travelled to and ran all WPAA events. After eight years and over 150 tournaments, however, he felt it was time to find someone else to take over these duties. In late 1982, he hired Neil Goldberg, a competitive light heavyweight puller and part-time armwrestling promoter, to take over the reins and run all WPAA events. Neil fit the bill – he had a background in the sport and was a good public speaker. At 27 years of age, and no significant family responsibilities yet, he was able to devote most of his weekends to the WPAA.

Neil ran all of the WPAA events between late 1982 and mid 1987. This period was the busiest in the WPAA’s existence, with more than 30 tournaments being held in some years. (In years with many events, only the top three or four finishers qualified to attend Worlds. In the early years, the top eight qualified.) In addition to this workload, Neil put on other sport tournaments for Steve on weekends when no armwrestling events were scheduled. Among these other sports were darts and “mini-tennis” (a game played with a Nerf ball and plastic racquets).

Although many WPAA tournaments were being held each year during the ‘80s, there was a downward trend in attendance levels, when compared to attendance in the ‘70s. Many more local events were being held by different promoters/organizations throughout the country, creating a visible attrition.

In late summer of 1987, Neil was involved in a major car crash. He was hit by a drunk driver and suffered a broken back. He was in the hospital recovering for several months. He had been in the middle of an adoption process at the time of the accident, and his life had been becoming busier in general. For this reason, he decided it was time to end his involvement with the WPAA and the sport of armwrestling. Interestingly, because of his abrupt departure, many people believed Neil actually died in the car crash. In actuality, he’s doing fine, working as a disc jockey in Baltimore.

With Neil’s departure, Steve had to find an alternative to continue to run WPAA regional events. Rather than using one person, Steve worked with different people in different parts of the country. The number of tournaments also had to be drastically reduced. Only 10 WPAA tournaments were put on in 1988.

In the late ‘80s, attendance levels at the WPAA World Championships were dropping. With fewer regional qualifying tournaments, less prize money at the World Championships, increased competition from other organizations, and the eventual elimination of television coverage, the event had become less of a draw.

WPAA tournaments continued to be held into the ‘90s. The final World Championship believed to have offered cash prizes was the 1993 Las Vegas event. WPAA World Championships were held for at least two more years, before the WPAA finally made its silent exit.

During the 21 years of its existence, the WPAA held approximately 500 events. Tournaments were organized in major malls and amusement parks throughout the United States, introducing organized armwrestling to several markets that had previously been unexposed to the sport. Well over $100,000 was donated to charity and virtually every elite armwrestler from the ‘70s or ‘80s competed in WPAA events. Many people consider Steve Simons and the WPAA to have done more than any other organization to increase the sport’s exposure and bring in new competitors prior to 1990. Not everyone agreed with all of the decisions Steve made, but few can disagree that he was a great businessman and is one of the very few people who has been able to successfully demonstrate the sport’s financial viability.

Although many WPAA tournaments were being held each year during the ‘80s, there was a downward trend in attendance levels, when compared to attendance in the ‘70s. Many more local events were being held by different promoters/organizations throughout the country, creating a visible attrition.

In late summer of 1987, Neil was involved in a major car crash. He was hit by a drunk driver and suffered a broken back. He was in the hospital recovering for several months. He had been in the middle of an adoption process at the time of the accident, and his life had been becoming busier in general. For this reason, he decided it was time to end his involvement with the WPAA and the sport of armwrestling. Interestingly, because of his abrupt departure, many people believed Neil actually died in the car crash. In actuality, he’s doing fine, working as a disc jockey in Baltimore.

With Neil’s departure, Steve had to find an alternative to continue to run WPAA regional events. Rather than using one person, Steve worked with different people in different parts of the country. The number of tournaments also had to be drastically reduced. Only 10 WPAA tournaments were put on in 1988.

In the late ‘80s, attendance levels at the WPAA World Championships were dropping. With fewer regional qualifying tournaments, less prize money at the World Championships, increased competition from other organizations, and the eventual elimination of television coverage, the event had become less of a draw.

WPAA tournaments continued to be held into the ‘90s. The final World Championship believed to have offered cash prizes was the 1993 Las Vegas event. WPAA World Championships were held for at least two more years, before the WPAA finally made its silent exit.

During the 21 years of its existence, the WPAA held approximately 500 events. Tournaments were organized in major malls and amusement parks throughout the United States, introducing organized armwrestling to several markets that had previously been unexposed to the sport. Well over $100,000 was donated to charity and virtually every elite armwrestler from the ‘70s or ‘80s competed in WPAA events. Many people consider Steve Simons and the WPAA to have done more than any other organization to increase the sport’s exposure and bring in new competitors prior to 1990. Not everyone agreed with all of the decisions Steve made, but few can disagree that he was a great businessman and is one of the very few people who has been able to successfully demonstrate the sport’s financial viability.

WPAA World Championship Locations

1974 - Busch Gardens, Los Angeles, CA

1975 - Culver City, CA

1976 - Culver City, CA

1977 - Houston, TX

1978 - Kansas City, MO

1979 - Kansas City, MO

1980 - Kansas City, MO

1981 - Kansas City, MO

1982 - Memphis, TN

1983 - Memphis, TN

1984 - New Orleans, LA

1985 - Detroit, MI

1986 – Las Vegas, NV

1987 - Toronto, ON, CANADA

1988 - Albuquerque, NM

1989 - Albuquerque, NM

1990 - Albuquerque, NM

1991 - Albuquerque, NM

1992 - Albuquerque, NM

1993 - Las Vegas, NV

1994 – Las Vegas, NV

1995 – Las Vegas, NV

1975 - Culver City, CA

1976 - Culver City, CA

1977 - Houston, TX

1978 - Kansas City, MO

1979 - Kansas City, MO

1980 - Kansas City, MO

1981 - Kansas City, MO

1982 - Memphis, TN

1983 - Memphis, TN

1984 - New Orleans, LA

1985 - Detroit, MI

1986 – Las Vegas, NV

1987 - Toronto, ON, CANADA

1988 - Albuquerque, NM

1989 - Albuquerque, NM

1990 - Albuquerque, NM

1991 - Albuquerque, NM

1992 - Albuquerque, NM

1993 - Las Vegas, NV

1994 – Las Vegas, NV

1995 – Las Vegas, NV

WPAA World Champions (Incomplete List)

1974

Lightweight - Marvin Myers

Middleweight - Clyde Farmer

Light Heavyweight - Bob Howell

Heavyweight - John Woolsey

Women's Open - Vicki Vodon

1975

Lightweight - Larry Kastrava

Middleweight - Jeff Schuitzle

Light Heavyweight - Jack Wright

Heavyweight - John Woolsey

Women's Open - Vicki Vodon

1976

Lightweight - Harvey Frank

Middleweight - Ron Bennett

Light Heavyweight - Al Turner

Heavyweight - Virgil Arciero

Women's Lightweight - Joanne Cronin

Women's Open - Mildred Choplick

1977

Lightweight - Harvey Frank

Middleweight - Johnny Walker

Light Heavyweight - Bob Howell

Heavyweight - Dan Mason

Women's Lightweight - Jackie Allard

Women's Open - Cindy Baker

1978

Lightweight - John Renfro

Middleweight - Johnny Walker

Light Heavyweight - Al Turner

Heavyweight - Dan Mason

Women's Lightweight - Kelli Green

Women's Open - Mildred Choplick

1979

Lightweight - Harley Maynard

Middleweight - Johnny Walker

Light Heavyweight - Rick Levine

Heavyweight - Cleve Dean

1980

Lightweight - Allen Fisher

Middleweight - Johnny Walker

Light Heavyweight - Alan Downing

Heavyweight - Dan Mason

Women's Lightweight - Fran Brzenk

Women's Open - Joan Schoebel

1981

Flyweight - Dave Patton

Lightweight - Allen Fisher

Middleweight - Johnny Walker

Light Heavyweight - Neil Goldberg

Heavyweight - Cleve Dean

Women's Open - Joan Schanke

1982

Flyweight - Dave Patton

Lightweight - Allen Fisher

Middleweight - Johnny Walker

Light Heavyweight - Eddie Long

Heavyweight - Cleve Dean

Women's Lightweight - Cheri Fiebig

Women's Open - Carol Molnau

1983

Flyweight - Dave Patton

Lightweight - Harley Maynard

Middleweight - Johnny Walker

Light Heavyweight - Rick Levine

Heavyweight - Cleve Dean

Women's Lightweight - Lucie Desaulniers

Women's Open - Carol Molnau

1984

Flyweight - Dave Patton

Lightweight - Allen Fisher

Middleweight - Johnny Walker

Light Heavyweight - Eddie Long

Heavyweight - Bobby Hopkins

Women's Lightweight - Christine Leclair

Women's Open - Carolyn Leibel

1985

Flyweight - Paul Cecchini

Lightweight - Dave Patton

Middleweight - Johnny Walker

Light Heavyweight - John Brzenk

Heavyweight - Bobby Hopkins

Women's Lightweight - Cheri Fiebig

Women's Open - Liane Dufresne

1986

Flyweight - Paul Cecchini

Light Heavyweight - Gene Tatti

Heavyweight - Keith Jones

Women's Lightweight - Christine Jaworski

Women's Open - Liane Dufresne

1987

Flyweight - Serge Usereau

Lightweight - Kevin Kelly

Middleweight - Ed McKenny

Light Heavyweight - George Gottschalk

Heavyweight - Gary Goodridge

Women's Lightweight - Nancy Locke

Women's Open - Liane Dufresne

1988

Women's (class unknown) - Paula Glick

1989

Light Heavyweight - Mike Ondrovic

Women's Lightweight - Candace Leith

1990

Middleweight - Jim Tambourine

Light Heavyweight - James Anderson

1991

Flyweight - Kevin Durant

Lightweight - James Anderson

Middleweight - Jim Tambourine

Light Heavyweight - Terry Corkran

1993

Flyweight - Tim Collins

Lightweight - Bob Brown

Middleweight - Kevin Bongard

Light Heavyweight - Bill Brzenk

Heavyweight - Bill Brzenk

Women's Lightweight -Elaine Blik

Women's Open - Elaine Blik

1994

Flyweight - Tim Collins

Lightweight - Dale Austin

Middleweight - Colt Middleton

Light Heavyweight - Terry Willis

Heavyweight - Eric Jury

Women's Lightweight - Amber Cooney

Women's Open - Cindy Dunn

Lightweight - Marvin Myers

Middleweight - Clyde Farmer

Light Heavyweight - Bob Howell

Heavyweight - John Woolsey

Women's Open - Vicki Vodon

1975

Lightweight - Larry Kastrava

Middleweight - Jeff Schuitzle

Light Heavyweight - Jack Wright

Heavyweight - John Woolsey

Women's Open - Vicki Vodon

1976

Lightweight - Harvey Frank

Middleweight - Ron Bennett

Light Heavyweight - Al Turner

Heavyweight - Virgil Arciero

Women's Lightweight - Joanne Cronin

Women's Open - Mildred Choplick

1977

Lightweight - Harvey Frank

Middleweight - Johnny Walker

Light Heavyweight - Bob Howell

Heavyweight - Dan Mason

Women's Lightweight - Jackie Allard

Women's Open - Cindy Baker

1978

Lightweight - John Renfro

Middleweight - Johnny Walker

Light Heavyweight - Al Turner

Heavyweight - Dan Mason

Women's Lightweight - Kelli Green

Women's Open - Mildred Choplick

1979

Lightweight - Harley Maynard

Middleweight - Johnny Walker

Light Heavyweight - Rick Levine

Heavyweight - Cleve Dean

1980

Lightweight - Allen Fisher

Middleweight - Johnny Walker

Light Heavyweight - Alan Downing

Heavyweight - Dan Mason

Women's Lightweight - Fran Brzenk

Women's Open - Joan Schoebel

1981

Flyweight - Dave Patton

Lightweight - Allen Fisher

Middleweight - Johnny Walker

Light Heavyweight - Neil Goldberg

Heavyweight - Cleve Dean

Women's Open - Joan Schanke

1982

Flyweight - Dave Patton

Lightweight - Allen Fisher

Middleweight - Johnny Walker

Light Heavyweight - Eddie Long

Heavyweight - Cleve Dean

Women's Lightweight - Cheri Fiebig

Women's Open - Carol Molnau

1983

Flyweight - Dave Patton

Lightweight - Harley Maynard

Middleweight - Johnny Walker

Light Heavyweight - Rick Levine

Heavyweight - Cleve Dean

Women's Lightweight - Lucie Desaulniers

Women's Open - Carol Molnau

1984

Flyweight - Dave Patton

Lightweight - Allen Fisher

Middleweight - Johnny Walker

Light Heavyweight - Eddie Long

Heavyweight - Bobby Hopkins

Women's Lightweight - Christine Leclair

Women's Open - Carolyn Leibel

1985

Flyweight - Paul Cecchini

Lightweight - Dave Patton

Middleweight - Johnny Walker

Light Heavyweight - John Brzenk

Heavyweight - Bobby Hopkins

Women's Lightweight - Cheri Fiebig

Women's Open - Liane Dufresne

1986

Flyweight - Paul Cecchini

Light Heavyweight - Gene Tatti

Heavyweight - Keith Jones

Women's Lightweight - Christine Jaworski

Women's Open - Liane Dufresne

1987

Flyweight - Serge Usereau

Lightweight - Kevin Kelly

Middleweight - Ed McKenny

Light Heavyweight - George Gottschalk

Heavyweight - Gary Goodridge

Women's Lightweight - Nancy Locke

Women's Open - Liane Dufresne

1988

Women's (class unknown) - Paula Glick

1989

Light Heavyweight - Mike Ondrovic

Women's Lightweight - Candace Leith

1990

Middleweight - Jim Tambourine

Light Heavyweight - James Anderson

1991

Flyweight - Kevin Durant

Lightweight - James Anderson

Middleweight - Jim Tambourine

Light Heavyweight - Terry Corkran

1993

Flyweight - Tim Collins

Lightweight - Bob Brown

Middleweight - Kevin Bongard

Light Heavyweight - Bill Brzenk

Heavyweight - Bill Brzenk

Women's Lightweight -Elaine Blik

Women's Open - Elaine Blik

1994

Flyweight - Tim Collins

Lightweight - Dale Austin

Middleweight - Colt Middleton

Light Heavyweight - Terry Willis

Heavyweight - Eric Jury

Women's Lightweight - Amber Cooney

Women's Open - Cindy Dunn

Researched and Written by Eric Roussin

This article would not have been possible without the help of John Woolsey, Steve Simons, and Neil Goldberg. All three granted the author extended telephone interviews.

This article would not have been possible without the help of John Woolsey, Steve Simons, and Neil Goldberg. All three granted the author extended telephone interviews.