Armwrestling Matches in the Cradle of Strongmen

A History of Armwrestling in Early 20th Century Quebec

During the golden age of strongmen around the turn of the twentieth century, one place seemed to produce more than its share of formidable strength competitors than anywhere else on earth: the Canadian province of Quebec. Why was this? It is believed that Quebec was a “cradle of strongmen” due to the lifestyle of the ancestry of the French-speaking population. Life during the early days of Quebec was hard. Many men worked seven days a week during the summer plowing the land and during the frigid winters they worked in the forest as lumberjacks. Physical strength was an integral part of life; great strength became revered. It is no wonder that this environment, combined with the availability of abundant natural, healthy foods, produced several impressive specimens of strength.

Armwrestling’s roots in Quebec dates back at least to the mid-18th century. The term “Tirer au poignet” (the French translation for “to armwrestle”) entered the popular lexicon in 1748, indicating that the activity was already becoming common. “Tir au poignet”, which literally translates as “pull with wrists” remains the standard translation among French-speaking Canadians. (The alternate term “bras de fer” (“arm of iron”) appears to have originated elsewhere.)

An early armwrestling anecdote involves a local politician by the name of Joseph Turcotte who travelled to a church in Saint-Maurice, Quebec, to make his case to voters in 1861. No one was interested in listening to what he had to say and he was told to leave. He answered that he was only there to sing, and he proceeded to sing everything he wanted to say. The parishioners admitted that he had a very nice voice, even nicer than the parish’s best singer Xavier Baron – a man who was also known for his great strength. Someone in the crowd yelled out “he may sing better than Xavier Baron, but I’m willing to bet that he won’t armwrestle him.” Mr. Turcotte responded that he was willing to pull Mr. Baron. This was considered to be brazen comment and the parishioners were eager to see him lose to the local strongman. It wasn’t long before someone went to get Xavier and a table and a couple of chairs were set up on the church’s front steps. Joseph was missing one arm, but his remaining arm was very strong. Before starting the match, he proposed an arrangement. He suggested they pull in a best two-out-of-three format. If Xavier won, Mr. Turcotte would leave and never come back. But if he won, all of the parishioners would vote for him in the upcoming election. Everyone agreed, and Mr. Turcotte proceeded to down Mr. Baron’s arm in consecutive matches. It is said that his election win was due to the support from this particular group of voters!

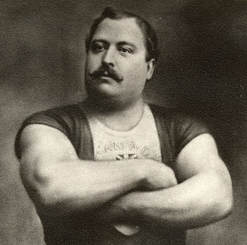

The man who best represented the strength of French-Canadians was Louis Cyr. Recognized by most for close to 20 years as the world’s strongest man, he was a hero among Quebeckers. Not only was he the greatest strength competitor of the era, he was also an incredible armwrestler. And though he did not often perform armwrestling displays in his strength shows, he always enjoyed partaking in the activity in social situations. He never lost.

Armwrestling was a popular test of strength during the 19th century, but due to its unofficial nature, it was not considered to be a sport. This began to change in February 1898, when Montreal’s leading newspaper “La presse” announced that a man by the name of Alfred Prévost declared himself Canadian Armwrestling Champion. He had recently travelled from nearby Roxton Falls to face A. Brien, a man reputed to have a very strong arm. They pulled in a best 3-out-of-5 format, and Mr. Prévost successfully defended his title.

La presse continued to provide armwrestling with coverage in its sports section whenever big matches were contested. People such as Ovila Chapleau, L. Thibault, A. Crevier, and Arthur Dandurand quickly made names for themselves at the turn of the century, each racking up long lists of victories. Almost all of these matches occurred in Montreal, Quebec’s largest city.

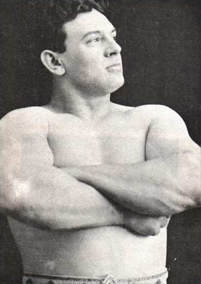

One competitor of particular note in these early years was Hector Décarie, a man who was beginning to make waves in the world of professional strongman contests. His first recorded major armwrestling win occurred on August 19, 1901, when he beat Mr. Chapleau – a man who was considered by many to be unbeatable. Hector proved everyone wrong, as he handed Chapleau his first-ever loss.

Hector only armwrestled a couple of matches, and once he beat Chapleau, he wasn’t able to find opponents who were willing to pull him for a wager that was large enough to interest him. The person he was most interested in pulling was Mr. Crevier, because he was unbeaten. Unfortunately, it appears that this match never materialized. Hector began being billed as the undisputed Armwrestling Champion of Canada, and it seems in these years few people argued that this assertion was incorrect.

In 1905, Hector Décarie and his brother Arthur decide that it was time to hold an official contest to crown Canadian Armwrestling Champions. There was interest among the top competitors, as well as from fans of the sport, for such a tournament. It was also intended to honour the many men who had engaged in the activity in unofficial settings over the past 150+ years.

The contest was first announced in La presse on August 1 of that year – it would be held at the end of the month over several evenings. With Hector not finding opponents and wanting to focus exclusively on the more lucrative strongman contests, he declared that he was retiring from the sport of armwrestling and would relinquish his title to the winner of the tournament. Three separate weight classes would be contested: lightweight (up to 160 lbs), middleweight (between 160 and 180 lbs), and heavyweight (over 180 lbs). The winners of each class would receive $50 and a medal. The entry fee would be $2. A single elimination format would be used, and each match would be a best 2 of 3 falls.

The contest announcement also provided an overview of the basic ways that matches were typically contested. There were three ways to armwrestle: the “straight pull”, the “half-hook”, and the “hook”. Straight pull matches were usually contested with elbows 15 to 18 inches apart, and technique played a bigger role. (Specifics are not given, but I expect this to be more of an outside or top roll style of armwrestling.) Hook matches were typically contested with elbows closer together – usually 12 to 14 inches. This style of pulling was preferred by many because it was thought to be a better measure of wrist and forearm strength. This smaller distance would be used for the tournament, though any pulling style would be permitted.

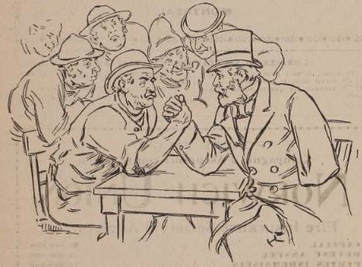

Armwrestling matches in Quebec 100+ years ago were contested a bit differently than they are contested today. While competing hands were clasped at the thumb (like now), the non-competing hands were typically laid flat on the table. Matches were contested sitting down. The elbows of the competing arms were set straight across from each other (some tables had grooves for the elbows). A straight line was drawn on the table between the two elbows and the objective was usually to pin the opponent’s arm all the way down to the table top, but occasionally it was simply to pull the opponent’s arm over a certain distance from the line.

Most matches were not contested through single falls, but usually 2 out of 3, and sometimes 3 out of 5. Individual pulls were timed, and if a fall was not recorded within the specified amount of time (usually 15 or 30 seconds), the pull was declared a draw and restarted. The process would repeat until a competitor successfully reached the number of pins required to secure a victory.

The first round of matches of the Canadian Armwrestling Championship took place on the evening of August 28th, 1905,at l’Hôtel Athlétique in the Saint-Henri neighbourhood of Montreal. The contest would extend over several nights, and each puller would face no more than one opponent per night. 32 competitors registered for the tournament in the four weeks leading up to the contest, but only 20 actually ended up taking part: 10 lightweights, 4 middleweights, and 6 heavyweights. Almost all of the top pullers of the day took part.

By the third night of the contest, August 30th, the middleweight champion was crowned. The winner was a Mr. Clairoux. The following evening Charles Tremblay won the lightweight title. And on Saturday, September 2nd, Arthur Dandurand won the Canadian heavyweight title.

Winners were encouraged to use their cash winnings as wagers against anyone who would want to challenge for their crown in the future. In other words, the contest was intended to be a one-time occurrence. One-off challenge matches would subsequently be held to determine if and when the titles would switch hands.

The way in which big armwrestling matches were organized is fascinating. While matches occurred in counties across the province, the majority of the headline matches occurred in Montreal, and the city’s newspapers were used to help arrange and publicize them. Oftentimes, a competitor would write into the paper and issue a challenge – either to a specific individual or to all-comers. The challenge would typically be accompanied by a wager. Competitors’ backers, or the competitors themselves would put up the money to bet on the outcome of the match. Many of the biggest matches involved bets of $50 or $100 (roughly $750 or $1,500 in 2018 dollars), but a few were contested for much more (one match organized in 1908 between Alfred Gingras and a man named Auger, two early champions, reportedly involved a wager of $1,100!). If the challenge was accepted, arrangements would be made to meet to iron out the match details. Many times, competitors would be accompanied by their managers.

A detailed contract would be developed that would include a variety of stipulations. In addition to standard details (e.g., date, time, location), competitors also had to agree on the format (2 out of 3, 3 out of 5, etc.), who would officiate, the duration of each round (i.e. pull), the amount of time between rounds, and the distance between the elbows (typically between 12 and 16 inches). It is clear that armwrestling techniques were already being developed, as some contracts stipulated whether or not the thumb could be capped, and in rare cases, whether the hands would be tied together to prevent them from coming apart. And of course, the contract included payment details. Usually there would be the matter of the wager (for which the money had to be provided by both sides in advance of the match), and in some cases a share of the gate receipts. Many people were willing to pay for the privilege of seeing high profile matches.

The timeline is a bit fuzzy with respect to when the Canadian light and middleweight titles changed hands, but more information is available to help identify when different men held the heavyweight crown. It seems Arthur Dandurand likely held the crown for two years before losing it to Jean-Baptiste Dubé on September 18th, 1907. A little over a month later, on October 30th, Dubé lost the title to Ovila Chapleau (the same man that Hector Décarie beat in 1901). Sometime in 1908 or 1909, Chapleau and Dubé had a rematch, and Dubé took back the crown. Finally, on June 25th, 1910, Théophile Massé beat Dubé.

Théophile Massé, a factory worker for Canadian Pacific, would remain champion throughout the second decade of the 20th century. During these years, Massé faced several opponents – each billed as the one who might finally beat him. But none of them did.

One match that Massé wanted badly was with Arthur Dandurand. The two had never pulled, and many thought Dandurand could beat Massé. Arthur’s supporters were wrong. When the two finally met on June 30th, 1915, Massé won.

The other man Théophile was eager to pull was none other than Hector Décarie. He started calling him out through La presse in 1917. Hector had retired from competition undefeated 12 years prior. He made his living as a travelling strongman, and he lacked the monetary incentive to pull Théophile. Training for a big armwrestling match was just not something on which he wanted to spend time. Hector did say that one day he would give Théophile his chance, but it would not be anytime soon. And so, Théophile would have to wait, and continue to take on any other challengers who were ready to wager upwards of $100.

One of Massé's toughest matches was with Joseph Desjardins of Hull, Quebec. The two pulled on January 19th, 1921, for a wager of $500 (close to $7,500 in 2018 dollars). It turned out to be one of the most hotly contested matches ever seen in the province. The format for the match was 2 out of 3, with each pull lasting a maximum of 25 seconds. Elbows were placed 16 inches apart. It took six pulls before Mr. Desjardins finally won a fall, and another six pulls before Mr. Massé was able to tie up the match. They then continued to pull an additional 35 times (!) without either opponent registering a win before the referee finally declared the match a draw. After a couple of hours of pulling, the crowd of 200 spectators was happy to recognize the two men as co-champions. However, because Théophile had not lost the match, the title of Canadian Champion did not change hands.

Just three months later, on April 18th, the biggest match of the era took place. Théophile’s longtime wish to face Hector Décarie would finally be realized. The match would be for a wager of $500. The two men recognized as Canada’s best pullers would finally pull to determine who the TRUE Canadian Armwrestling Champion was.

Unfortunately, in his desire to make the match happen, Massé agreed to Décarie’s terms. Théophile’s preference was to pull at a distance of 15” between the elbows (which coincidentally is the exact distance between the middle of the elbow pads on the current WAF table) and with a time limit of 25 seconds per pull. Décarie preferred a smaller distance and a time limit of 15 seconds. He knew that if he was going to win, it would be quickly with a hook. If Théophile managed to stop him, he would likely run out of gas. He felt he could hold for 15 seconds and get a restart, but any longer and he might be pulled across the table.

Fans of the sport speculated that Massé’s decision to accept Décarie’s terms would prove to be a mistake. It turns out they were right. Hector won the match in two straight pulls. Théophile had lost his title in the biggest armwrestling match ever held in Canada.

The person who most wanted a match with Hector was Théophile Massé. He wanted a chance to pull Mr. Décarie a second time, but this time with stipulations that were equally fair to both men. Through La presse, he tried on at least a couple of occasions to call Hector out for a match, without success. Eventually, he offered to pull Hector for an amount of his choosing, to which Mr. Décarie responded that he was interested, but at 48 years of age he needed some time to train for the match. Several months passed before Théo reached out to Hector once again, and this time received no response. So in late 1928 Théophile proclaimed himself the Champion of Canada. He had pulled for seven years billed as “the former Canadian Champion” -- he now once again started being billed as the current Canadian Champion. It does not seem as though Hector minded. In one of his public refusals to pull Mr. Massé (due to insufficient incentive) he said he would be willing to concede the title, because he respected Théophile’s abilities. Perhaps Hector was “paying it forward”, the same way in which Louis Cyr had bequeathed his title of world’s strongest man to him when they tied in their strongman match back in 1906. Louis’ health was rapidly declining and he recognized that Hector was a worthy successor for the title.

Based on the sport’s coverage in the local newspapers of the era, it appears armwrestling matches were at their peak in popularity during the 1920s. At a few points during this decade, armwrestling matches were being promoted on an almost weekly basis. Sometimes the matches were run in conjunction with wrestling and boxing bouts, and sometimes they were run in conjunction with strongman contests. But the biggest matches were generally organized as separate events.

Hundreds of matches took place over the course of the decade, but a handful of matches garnered more attention than others:

December 18th, 1924 – Henri Groulx, a 150-lb blacksmith from Lachine, Quebec, faced Philippe Fournier, a young up and coming strongman from Grand-Mère, Quebec. There was considerable excitement because Mr. Groulx had not had a loss in 75 straight matches, and 19-year old Mr. Fournier was a rising superstar in the world of strength. Philippe won the match, along with $300.

December 23rd, 1924 – Philippe Fournier met Wilfrid Latour, a champion strongman who outweighed him by 25 lbs. Only five days after his win over Henri Groulx, Philippe pulled Wilfrid to a draw in front of a crowd of 400. Mr. Fournier would go on to be one of the most active pullers of the decade. It is said that for a while, he made most of his living off the money me won in armwrestling matches (he would bet on himself).

December 15th, 1925 – Théophile Massé faced Placide Laframboise. Placide was coming off his win over Wilfrid Latour two months prior. He outweighed Théophile by 40 lbs and was the favorite heading into the match. But Mr. Massé silenced the crowd by taking the match with a score of 3-1. Their hands were tied together for all of their pulls.

March 28th, 1928 – Théophile Massé faced yet another rising star in Léonide Marleau, from Valleyfield, Quebec. Mr. Marleau had handily beaten Henri Groulx the previous fall and was the favorite heading into the match with Mr. Massé. Perhaps people were starting to underestimate Théophile as he was reaching 40 years of age? Regardless, he proved he was still very capable, beating Léonide by a score of 3-2.

Armwrestling’s popularity in Quebec started to wane in tandem with strongman contests. There are a few possible reasons for this. In the 1920s, weightlifting associations were starting to form and there was a move towards the adoption of standardized lifts and rules. The strongman contest format fell out of favour. As well, wrestling and boxing were exploding in popularity, and had much more to offer young men (in terms of potential fame and riches) who in years previous would have likely shown an interest in pursuing strength sports.

One of the last major matches to draw media attention was a match for the Canadian Championship between Théophile Massé (title holder) and Wilfrid Latour on October 16th, 1930. Massé’s title was on the line and he was facing an able opponent. But once the action started, Mr. Massé made quick work of Latour, winning the match in three straight pulls. Mr. Latour took the loss very well. He immediately stood up to congratulate Théophile and shake his hand while announcing to everyone “Mr. Massé is the champion and he is much better than me”. This prompted someone in the crowd to stand up and express his admiration to Mr. Latour: “A spirit like the one displayed by Mr. Latour is what makes a true Canadian man”. A great time was had by all and the night ended with everyone joining in song! The festivities served as a fitting end to the golden era of Quebec armwrestling.

Researched and Written by Eric Roussin

Originally published in October 2017 - Revised, updated, and expanded in June 2018