From Common Working Tool to Classic Test of Functional Strength:

The Origin of the Wheelbarrow Contest

At the beginning of the 20th century, it was believed by many that the combination of rapid urbanization and industrialization was responsible for the “softening” of the population. One such place where this was a common opinion was in Montreal, Canada, whose population increased almost 400% in forty years between 1871 and 1911. Fewer and fewer jobs required demanding physical labour. This was theorized to be one of the main reasons for why there were relatively few French-Canadian athletes capable of successfully competing at an international level.

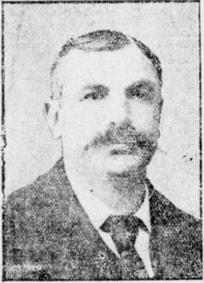

One man who was concerned with the weakening of the French-Canadian populace was Dr. Joseph-Pierre Gadbois. He was a big proponent of health and physical fitness, and when he became a journalist for La presse, Montreal’s leading newspaper, he made a point to use this platform to share his views.

Dr. Gadbois was convinced that there were still many strong men who lived in and around the city: farmers, labourers, blacksmiths, butchers, etc. They didn’t have the opportunity to display their strength to the masses and he wanted to find away to shine a spotlight on them. Through regular coverage of French-Canadian athletic achievements, Dr. Gadbois believed more and more people would be motivated to be physically active.

One of his ideas was a wheelbarrow pushing contest. Most strength contests of the period were the domain of professionals – men who trained with specialized equipment. The vast majority of people did not have access to things like barbells and dumbbells. However, almost everyone had experience pushing a wheelbarrow. Dr. Gadbois considered the wheelbarrow to be a great tool for testing functional strength, and it would allow working men to compete on a more equal footing with strongmen. While professional strongmen might have more strength, working men might have more experience in the balance required for maneuvering a wheelbarrow.

Dr. Gadbois believed the contest would be the first of its kind. A teaser ad appeared on the front page of the December 4, 1907 edition of La presse. It announced that the wheelbarrow contest was coming but provided no details. Readers were encouraged to keep reading regularly to find out more about it. Over the following days, articles appeared explaining the purpose of the contest to build up public interest, but still no specific details were shared.

In mid-December, just when the newspaper was about to announce the details of the contest, it decided to first ask readers if they could guess what the contest would entail. The newspaper encouraged readers to keep the purpose of the contest in mind: to test natural strength in the simplest way possible, and to make a popular sport out of something traditionally viewed as hard work. An award would be given to the reader whose idea that most closely matched Dr. Gadbois’.

Ideas immediately started pouring into La presse from all over Quebec, Ontario, and the northeastern states. And over the course of the following month, the newspaper published almost all of them (more than 100!). Everyone had a different idea of exactly how the contest should be run. Opinions differed on:

- Whether the wheelbarrow should be pushed in a straight line, in a circle, or in some other manner.

- Whether the contest should be about maximum weight pushed for a given distance, or maximum distance for a given weight.

- Whether a set distance should be covered with the wheelbarrow, or the competitor should continue as far as possible.

- If a set distance, what the distance should be.

- Whether a flat surface should be used, or a terrain with various obstacles.

- Whether the wheelbarrow should be pushed up an incline, down a decline, or both.

- If there was to be an incline or decline, what the angle should be.

- What should be loaded in the wheelbarrow (e.g. bricks, rocks, iron rods, bags of salt, barrels, etc.).

- Whether competitors should have access to different size wheelbarrows based on their height and weight.

- Whether the wheelbarrow should be loaded to different weights based on the competitor’s size.

- Where the location should be held (e.g. various parks, drill halls).

- What the weight of the load should be (if a set weight is desired).

- Whether the wheelbarrow should be pushed or pulled.

- How the weight should be positioned in the wheelbarrow.

- Whether the wheelbarrow should be loaded by the competitors or by someone else.

- Whether the weight should be balanced or unbalanced (e.g. a barrel of water filled halfway would be significantly harder to balance than a dead weight).

- The type of terrain (e.g. sand, gravel, wooden planks, snow, ice).

- Whether or not wrist straps should be allowed to make it fair to competitors with shorter fingers.

- Whether or not the wheel should be jammed so that it doesn’t turn. (!)

On January 11th, 1908, the date and location of the contest was announced. It would be held the evening of January 30th, in Sohmer Park, an amusement park in Montreal with a pavilion that could accommodate up to 8,000 people. This information was welcomed by readers, but they were most interested in reading about how the event would be contested.

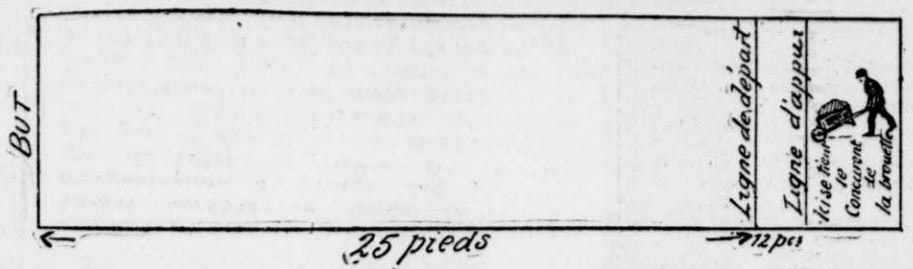

Finally, on January 18th, the basic contest rules were published. Competitors would need to walk the length of a flat, 4-foot wide and 25-foot long platform, without setting down the wheelbarrow with as much weight as possible. Any successful attempt of 2,500 lbs or more would be considered a world record (no official record existed). The winner of the idea submission contest was a Mr. Amédée Grenier, of Montreal, whose idea was almost identical to the idea conceived by Mr. Gadbois and La presse’s contest organizing committee. He was awarded a cheque for $5 (equating to more than $100 in 2019 dollars).

Registration for the contest opened on January 20th. It was free to enter – participants simply needed to provide their name, age, address, occupation, height, weight, any strength accomplishments of note, and a photograph (anyone without a photograph could stop by La Presse’s offices to have one taken). The contest was open to all French-Canadians, including those living stateside. The event would be contested over several weeks, starting on January 30th and continuing each subsequent Thursday night until a winner was crowned.

La presse published an updated list of entrants each day leading up to the contest. Full competitor details were shared, which prompted many predictions to be made. Some of the early favourites, based on their reported achievements, reputation, and/or size, included the following men:

Léon Beaupré was a butcher and was widely recognized as the strongest butcher in the city. He had once pushed a load of approximately 1,800 lbs of meat in a wheelbarrow, which would have been significantly harder to balance than a similar wheelbarrow filled with lead ingots (bars). A big man for the time, he was 5’11” and weighed 225 lbs.

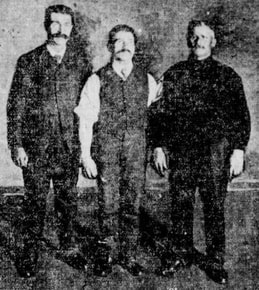

Nazaire Belzil was a Montreal firefighter, and believed to be the strongest among them. He was no stranger to sport, having dabbled in wrestling, weightlifting, and even track and field events. Prior to becoming a firefighter, he had a very physically demanding job as an employee of a brick manufacturer. He was reputed to have previously pushed a wheelbarrow loaded with 2000 lbs 180 feet! One of the contest’s largest competitors, he stood 6’4” and weighed 275 lbs.

Referred to as both The Wheelbarrow Demon and The Wheelbarrow Lion, Joseph Vanier, a farmer from nearby Vaudreuil, Quebec, was the heaviest man in the contest. At 6’3½” tall, he weighed a whopping 344 lbs. He once pushed a wheelbarrow with a load of 1,100 lbs over a terrain of sand six inches deep!

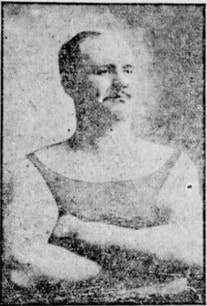

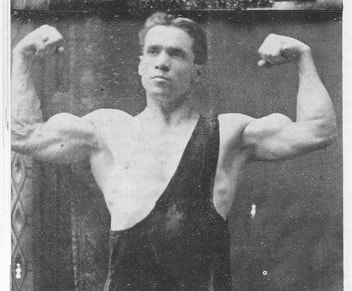

At 5’8” and 177 lbs, Arthur Dandurand was far from being the biggest man in the contest, but his muscular development was perhaps the most impressive. He was also well-known for his various feats of strength, and had won the first ever Canadian Armwrestling Championship in September, 1905.

Detailed contest rules were finally shared on January 25th:

- Each competitor would be free to load his wheelbarrow as he wished (or have it loaded by someone else).

- The wheelbarrow would be loaded with lead ingots, with each ingot weighing approximately 60 lbs. The actual weight was to be measured once a successful attempt was achieved.

- The competitor would be allowed to lift the wheelbarrow to test the load, to determine if more weight should be added or some should be removed. But once the competitor took a step past the start line, the attempt would be considered official.

- There would be a 12” area before the start line for competitors to test the weight and their balance. The wheelbarrow could be picked up and set down as many times as desired in this area, as long as the start line was not crossed.

- The wheelbarrow handles would be small, so as not to disadvantage shorter-fingered competitors.

- Competitors would have the option to add tissue or tape to the handles to make them thicker or easier to grip, but wrist straps would be prohibited.

- The wheelbarrow’s legs would not be allowed to touch the floor during the attempt; however the competitor could take pauses as desired if the wheelbarrow was not set down.

- Tar would be placed at the bottom of the wheelbarrow’s legs, so that any touching of the platform would be noticed by the judge. Said tar would be cleaned from the platform between attempts.

- A metal plate would be placed on the floor in the starting area so that the barrow legs would not damage the wooden platform.

- The judge would be Dr. Gadbois and his decision would be final.

The big news that everyone was waiting for was also announced: the prizes. There would be cash prizes to the top 15 finishers: $100 for first, $50 for second, $25 for third, $15 for fourth, $10 for fifth, $5 for sixth through fifteenth.

The announcements of the detailed rules and prizes prompted many more people to sign up – 218 in all by the time registration closed on January 28th. This figure significantly exceeded the contest organizers’ expectations and so there was a need to make a few adjustments to the format. Competitors would be arranged into groups and each group would compete in a single night. The top performers would be identified and invited back for their second attempts. The best performers of the second round would be invited back for the grand finale. At the conclusion of the contest, the competitor who had made the heaviest successful attempt, whether it happened in the first, second, or final round, would be declared the winner.

Those who had hoped that some of the area’s professional strongmen – people such as Louis Cyr’s successor Hector Décarie and friend Horace Barré – were disappointed to see that they had not registered for the contest. Nevertheless, the contest did include many of the reputedly strongest men in the region and was sure to be exciting.

Sohmer Park attendees on opening night would be treated to more than just impressive displays of strength: there would also be a full orchestra, a juggling and balancing act, and film shorts form Europe peppered throughout the evening. General admission was set at 25 cents. For 10 cents more, spectators could watch the action from the gallery. Assigned seating was also available in the first six rows at a price of 50 cents, while those who really wanted to be up close could pay $2 to be on the stage. Proceeds would be given to a committee tasked with organizing the Canadian delegation of athletes that would be travelling to Rome later in the year to compete in an international gymnastics competition.

La presse also decided to impose a $2 entry fee for competitors, to be refunded at the end of the contest if they showed up and followed the rules. This was to weed out people who simply signed up to see their name in the newspaper (those who had no real intent of competing), as well as those who may had come to realize they stood no chance of winning among such a strong group of men. Serious competitors had to stop by La presse’s offices prior to the contest to pay their $2 and obtain their athlete admission pass.

The list of the 30 competitors called upon to make their opening attempts on the first night was selected at random and published in the La presse on January 29th. It was clearly stated that if any of the 30 men did not attend, they would be eliminated from the contest. Three of the early favourites were on the list: Léon Beaupré, Nazaire Belzil, and Pierre Vermette, resulting in considerable anticipation.

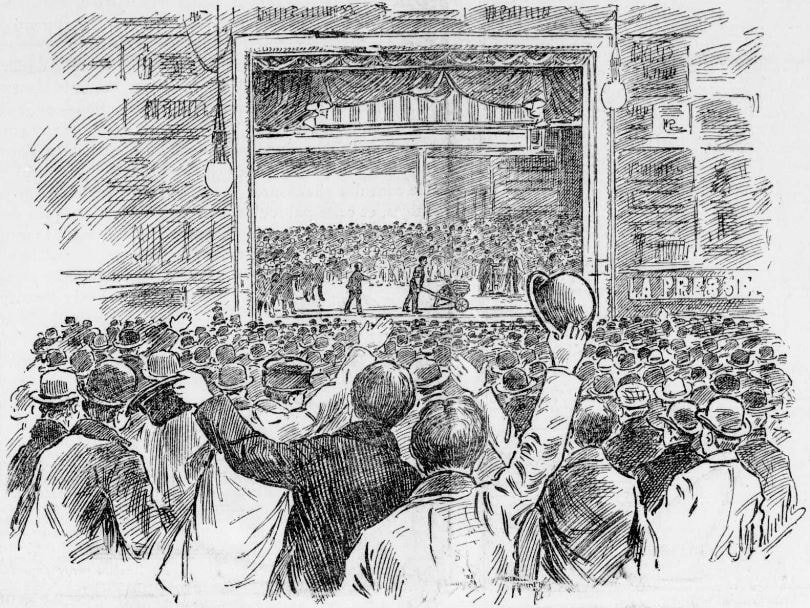

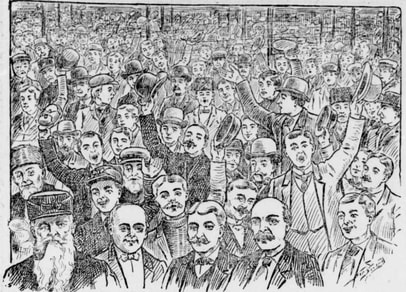

As the organizers had hoped, there was a massive turnout for the opening night of the contest, with thousands of people attending to cheer on the participants. Audience members enjoyed speculating on the outcome of each attempt, and lots of bets were placed.

It became clear early on that everyone might be in for a long night, because this first competitor lost his balance just a few feet into his attempt and 1,200 lbs of lead ingots toppled onto the floor! But things quickly improved with the next two competitors making successful attempts with a little under 1,000 lbs. The crowd roared its approval.

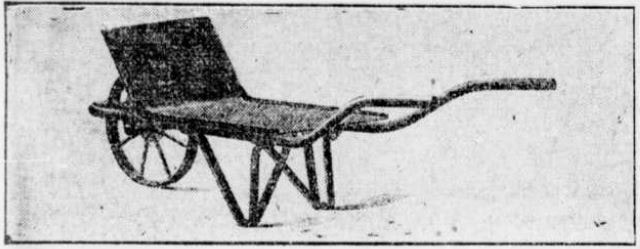

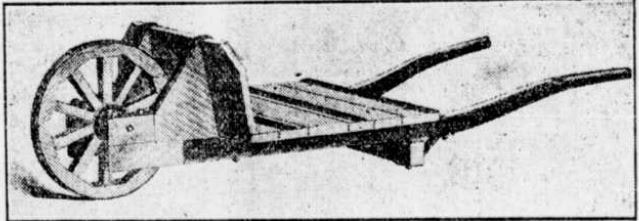

Three types of wheelbarrows were made available for use, each of a different style and resulting in a different feel for the competitors. One was made of metal, and had legs, another was made of wood, and was legless, and a third looked more like a miniature truck. Competitors were free to use whichever one they pleased.

The fourth competitor, 22-year-old chauffeur Adélard Hudon, opted to use the wheelbarrow that looked like a truck. Upon a successful attempt with a little over 1,316 lbs, he dropped the wheelbarrow to the floor and it broke under the impact. His would be the one and only attempt where this wheelbarrow would be used.

Motorman Joseph Allain, another competitor with many supporters, crossed the platform with 1,800 lbs. At a point he believed he had walked 25 feet, he dropped the wheelbarrow, only to learn that he was a couple of inches short! Luckily, he would have another chance in the second round.

When it was Nazaire Belzil’s turn, he lifted the wheelbarrow up and down several times prior to beginning his walk and asked the loaders to keep adding weight, to the audience’s delight. Finally, when he was up to a weight that he estimated to be approximately 1,900 lbs, be began his attempt. Completing the task with apparent ease, he was disappointed to find out that the load turned out to weigh only 1,796 lbs.

Léon Beaupré experienced some bad luck. When beginning his attempt, the wheel got stuck in a groove left by a previous contestant, which caused him to lose his balance and have all 28 lead ingots topple to the floor. He too would have another chance in round two.

When all was said and done, 19 competitors made their first attempts, while 11 did not show up and were therefore eliminated from the contest. Nazaire’s lift of 1,796 lbs was the heaviest successful attempt of the evening. The next two were more than 400 lbs lighter: Louis Jobin with 1372½ lbs and Adélard Hudon’s attempt of 1316¾ lbs. Mr. Belzil was the clear standout, and his mark was the one that everyone would be chasing going forward.

Following the first night of the contest, a few adjustments were made by the organizing committee to make things run more smoothly. It became clear that the strongest men could easily push a wheelbarrow loaded with 20 lead ingots (representing approximately 1200 lbs). As such, to accelerate the process, a decision was made that 1200 lbs would now be the minimum load, and that anyone who was not successful with at least this much weight in their first attempt would be eliminated from the contest. Another change was that a larger wheelbarrow would be used for the second evening – one that was both wider and longer. This was to make the wheelbarrow more stable so that strength became more of a limiting factor than balance. Some sheet metal would also be placed the length of the platform, to minimize both the damage caused by the wheelbarrow when it was dropped and the formation of grooves made by the wheel.

At the competitors’ urging, spectator admission fees were lowered for the second evening of the contest: 10 cents for general admission, or 20 cents for those who wanted to be in the gallery. These were the standard admission prices for shows at Sohmer Park and would allow even more people to attend.

Based on the expectation that once again several registered competitors would not attend, 50 men were randomly selected and summoned for the second night of the first round. The list included many of the bigger competitors, but none of the contest favourites.

On February 6th, a couple thousand people went to Sohmer Park for the big show. Everyone had their opinion on who would win and there were lively discussions throughout the evening. On average, heavier loads were transported across the platform than those from the first night. A handful of men even managed to take several steps with loads of around 1,800 lbs, which would have beat Mr. Belzil’s mark, but none could make it the entire 25 feet. The best successful attempt of the night was of 1,748 lbs, made by Pierre Gosselin, a 277-lb labourer.

As had occurred during the first evening of the contest, many competitors did not show up to make their opening attempts and were consequently eliminated from the contest. The organizing committee was hopeful that they could finish off the first round on the third night of the contest, so they called on all remaining competitors to attend Sohmer Park on February 13th.

The minimum load was once again raised. This time by 25% to roughly 1,500 lbs. There were lots of people who would be making their opening attempts, but the person most people wanted to see was Mr. Vanier. His supporters were very confident that he would lift more than Nazaire.

A new wheelbarrow was available to competitors on the third night, which generated a lot of chatter among the men who had made their attempts on one of the first two evenings. This was because it became quite clear that it was easier to maneuver. Not surprisingly, all the competitors opted to use this new wheelbarrow, and the results were significantly improved. In fact, by the end of the evening, nine of the top ten successful attempts in the contest were made on this third night.

The first competitor to surpass Mr. Belzil’s attempt was Avila Lavoie, a cook who weighed just 180 lbs. He was the 18th competitor to make a trip to the platform that night and his effort was met with tremendous applause. Three more men would go on to also eclipse Nazaire’s mark: carrier Joseph Desroches, 280-lb labourer Aquila Monette, and the man everyone expected to move a lot of weight, big Joseph Vanier. His was the top lift of the evening (and the contest so far), with a haul of 1,971 lbs.

There was considerable excitement caused by the last competitor of the night. Arthur Dandurand, the armwrestling champion, had the wheelbarrow loaded to 1,972 lbs – one pound heavier than the top haul made by Mr. Vanier. Dandurand got the weight up, started walking, and made it almost all the way across, only to drop the wheelbarrow three feet from the finish line!

Nazaire was not worried about what he witnessed that night. He felt he wasn’t anywhere close to his limit with his first attempt and he was confident he’d be able to haul much more – especially with the new wheelbarrow. His supporters were equally convinced and were willing to bet with anyone that their man would beat Vanier in the second round, but apparently there were no takers.

Due to time constraints, a dozen or so competitors did not get a chance to make their first attempts that night. They would get their chance the following week, and the second round of attempts would get underway the same night.

For the fourth night of the contest, held on February 19th, the minimum load was raised once again: this time to approximately 1,750 lbs (or 30 lead ingots). Attendance was expected to be bigger than ever because the second round would be starting.

First up were the few competitors who had yet to make their first attempts. No records were broken, however three men managed to break the top 10.

Standings at the conclusion of the first round:

1st – Joseph Vanier – 1,971 lbs

2nd – Aquila Monette – 1,855 lbs

3rd – Avila Lavoie – 1,848 lbs

4th – Joseph Desroches – 1,846 lbs

5th – Nazaire Belzil – 1,796 lbs

1st – Joseph Vanier – 1,971 lbs

2nd – Aquila Monette – 1,855 lbs

3rd – Avila Lavoie – 1,848 lbs

4th – Joseph Desroches – 1,846 lbs

5th – Nazaire Belzil – 1,796 lbs

After a brief intermission, it was time for the start of the second round. Competitors were split into two groups, with half being called to compete the first evening, and the remainder to compete the following week.

Mr. Belzil was the third man to make his second attempt, and he did not disappoint. He blew past Vanier’s mark by nearly 200 lbs with a haul of 2,141! The crowd went crazy: Nazaire was a local boy, while Vanier was an out-of-towner, so it’s not surprising that he had the largest share of supporters. But he would not be the only one to beat Vanier that night. Three other men – Pierre Beaulieu, motorman Moïse Charbonneau, and Pierre Gosselin – also made successful attempts with more than 2,000 lbs. Mr. Gosselin’s haul of 2,148 lbs was the best of the evening, exceeding Nazaire’s by seven pounds. They both loaded their wheelbarrow with 37 lead ingots, but not the same ones. While each ingot weighed roughly 60 lbs, some weighed a bit more and some weighed a bit less.

Mr. Belzil was the third man to make his second attempt, and he did not disappoint. He blew past Vanier’s mark by nearly 200 lbs with a haul of 2,141! The crowd went crazy: Nazaire was a local boy, while Vanier was an out-of-towner, so it’s not surprising that he had the largest share of supporters. But he would not be the only one to beat Vanier that night. Three other men – Pierre Beaulieu, motorman Moïse Charbonneau, and Pierre Gosselin – also made successful attempts with more than 2,000 lbs. Mr. Gosselin’s haul of 2,148 lbs was the best of the evening, exceeding Nazaire’s by seven pounds. They both loaded their wheelbarrow with 37 lead ingots, but not the same ones. While each ingot weighed roughly 60 lbs, some weighed a bit more and some weighed a bit less.

Gosselin’s lift of 2,148 was done in dramatic fashion. At the 17-foot mark, he started to lose his balance, and a few ingots fell out of the barrow. He supported the barrow with his thighs while the ingots were placed back in, before he continued on to finish his walk! He had to return to the stage three times to wave to the amazed crowd.

Léon Beaupré, the butchers’ champion, was well on his way to also completing a walk with 2,146 lbs, but he ran into some bad luck when, at about the halfway mark, the wheelbarrow’s wheel cracked a weak spot in the platform and got stuck. However, given his performance up to that point he was reassured he would be invited back for the third and final round.

The first night of the second round having shaken up the leaderboard, many people wondered just how much weight the strongest competitor would be able to push across the platform. Would someone be able to surpass the 2,500-lb mark and earn the world record? Most believed yes, and with many big names yet to make their second attempts, some felt it might happen before the final round.

The minimum load was once again raised for the remaining attempts of the second round. The minimum would be 32 lead ingots, or roughly 1,850 lbs. Competitors who weren’t confident that they could lift and push this weight were encouraged to stay home, as it was fully expected that the minimum would be raised yet again for the final round.

On the evening of February 26th, the number of failed attempts exceeded the number of successful ones. But given the minimum loads were so heavy all competitors were applauded for their efforts, regardless of their individual results.

Three hours into the action, three men had successfully crossed the platform with more than 2,000 lbs: Euclide Poulin, a longshoreman, William Leber, the only competitor in the field who worked a desk job, and Joseph Geoffrion, a mechanic who weighed only 158 lbs! But it is when Aquila Monette was successful with a weight of 2,233 lbs, or 85 lbs heavier than Mr. Gosselin’s mark, that the audience screamed the loudest. Before the night would be done, Arthur Dandurand would also be successful with a haul of 2,063. Dr. Gadbois was so impressed with Dandurand’s physical development that he asked him if he would be willing to flex his muscles for the audience. Arthur happily obliged.

It was getting late and it was announced that there would only be time for one more competitor: Joseph Vanier. He was the leader after the first round – everyone wanted to know if he would reclaim the lead at the end of the second. He had his wheelbarrow loaded with 39 ½ ingots and then began his walk. He made it all they way with 2,297 lbs!

The final round of the contest had been scheduled to occur one week later on the evening of Wednesday, March 4th. But there was a small problem: 20 or so men had yet to make their second attempts. There was no interest in pushing the final round back another week, so a special private session was held on March 2nd to finish off the second round. Of the 20 men, only 10 showed up for this special session, and while no one made it into the top ten standings, five did haul enough to be invited back on Wednesday. The minimum weight for the final round would be approximately 2,000 lbs (35 lead ingots).

Standings at the conclusion of the second round:

1st – Joseph Vanier – 2,297 lbs

2nd – Aquila Monette – 2,233 lbs

3rd – Pierre Gosselin – 2,148 lbs

4th – Nazaire Belzil – 2,141 lbs

5th – Euclide Poulin – 2,092 lbs

6th – William Leber – 2,090 lbs

7th – Moïse Charbonneau – 2,088 lbs

8th – Pierre Beaulieu – 2,078 lbs

9th – Arthur Dandurand – 2,063 lbs

10th – Joseph Geoffrion – 2,033 lbs

1st – Joseph Vanier – 2,297 lbs

2nd – Aquila Monette – 2,233 lbs

3rd – Pierre Gosselin – 2,148 lbs

4th – Nazaire Belzil – 2,141 lbs

5th – Euclide Poulin – 2,092 lbs

6th – William Leber – 2,090 lbs

7th – Moïse Charbonneau – 2,088 lbs

8th – Pierre Beaulieu – 2,078 lbs

9th – Arthur Dandurand – 2,063 lbs

10th – Joseph Geoffrion – 2,033 lbs

Of the 218 initial registrants, 36 had made it to the final round to compete for the top 15 positions and prize money. The contest organizers wanted to conduct the entire round in a single evening. As such, the contest would start 30 minutes earlier, and there would be no other entertainment at Sohmer Park the evening of March 4th (i.e. no variety acts or film shorts). General admission rates would remain the same, however, as was done for the first evening of the contest, there would be 300 special seats onstage available for $1 each for those who wanted to be as close to the action as possible.

To minimize the likelihood of mechanical problems, a new platform made of hardwood was built, and the wheelbarrow was reinforced. The organizers were prepared to let remaining competitors decide whether the final round should consist of one or two attempts. They were happy to go along with whatever the majority of the competitors wanted. Not surprisingly, most wanted two attempts, so this was how the contest was run.

An estimated 5,000 people attended the final night of the contest – the biggest turnout of the entire series. Everyone was eager to see who would win. Would it be Vanier? Belzil? Monette? Someone else? Those willing to stay until the end of the night would be the first to find out.

To minimize the likelihood of mechanical problems, a new platform made of hardwood was built, and the wheelbarrow was reinforced. The organizers were prepared to let remaining competitors decide whether the final round should consist of one or two attempts. They were happy to go along with whatever the majority of the competitors wanted. Not surprisingly, most wanted two attempts, so this was how the contest was run.

An estimated 5,000 people attended the final night of the contest – the biggest turnout of the entire series. Everyone was eager to see who would win. Would it be Vanier? Belzil? Monette? Someone else? Those willing to stay until the end of the night would be the first to find out.

The competitor order was randomly determined. Joseph Vanier, who had to wait until the end of the evening to make his second attempt one week earlier, was one of the first ones up in the final round. He didn’t waste any time to make a statement. He bested his previous mark by almost 500 lbs with a haul of 2,773! It was the first successful attempt of more than 2,500 and thus was a new world record! (To say that Mr. Vanier was having a big week would be an understatement. On top of his record lift, he had gotten married just two days earlier!)

Mr. Vanier’s record stood for just a few hours. It looked as though Nazaire Belzil might beat him when he attempted 3,011 lbs, but he lost his balance. A while later, Aquila Monette bested Vanier with a haul of 2,853 lbs, and about 15 minutes later, 250-lb Moïse Charbonneau raised the record again to 2,968! His mark would turn out to be the best of the first attempts of the final round.

At this point, it was already past 3am, but, as originally announced, the action would keep going until there was a winner. Though it was a winter weeknight, almost everyone stayed to see how things would play out.

Once again, Mr. Vanier was one of the first up. He wanted the wheelbarrow loaded to 3,500 lbs, but the loaders were having trouble loading just 3,241 (55 ¾ ingots) as it was already overflowing. He lifted the wheelbarrow, but it toppled before the start line. So the wheelbarrow was loaded again, and once again he lifted it and the ingots started toppling out. The referee, growing frustrated by the length of the contest, said that if the wheelbarrow toppled again, Vanier would be eliminated. (This wasn’t the original rule, which had stated that the wheelbarrow could be loaded as many times as desired prior to crossing the start line.) The wheelbarrow was carefully loaded up once again to 3,241 lbs. Joseph got it up, walked quickly across the platform… but tripped at the 21-foot mark. His eagerness to get his attempt over with ended up costing him the contest title.

The next competitor was none other than Nazaire Belzil. He also decided to attempt a haul of 3,241 lbs. There was one difference, though. He was successful! He had likely assumed this weight would be sufficient to win the contest, as Vanier was seen by most to be his main competitor. Few expected what would happen a couple of hours later….

Moïse Charbonneau was one of the last competitors to take his second attempt. He had the wheelbarrow loaded up with 55 ¾ ingots – the same number that Mr. Belzil had loaded for his record haul. But there was a small but significant difference. While the number of ingots was the same, they were not the exact same ingots. As the ingots varied slightly in weight from one to another, the total weight of the wheelbarrow was also a bit different. Mr. Charbonneau successfully completed his attempt, only to find out that his achievement bested Nazaire’s by five pounds! A few competitors made their attempts following Moïse, but none of them challenged him. Moïse Charbonneau was the winner of the contest, and he received a standing ovation the likes of which hadn’t been seen since opening night!

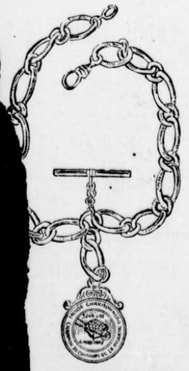

It was 7am, and understandably, the organizers were not interested in rushing an awards ceremony at that time. All of the winners would be invited back to Sohmer Park the Friday evening of the following week to be properly recognized. The top 15 finishers would receive their cheques, and Mr. Charbonneau would receive a medal.

Final Standings:

1st – Moïse Charbonneau – 3,246 lbs

2nd – Nazaire Belzil – 3,241 lbs

3rd – Joseph Allain – 2,951 lbs

4th – Alexandre Duchesne – 2,950 lbs

5th – Aquila Monette – 2,911 lbs

6th – Euclide Poulin – 2,899 lbs

7th – Pierre Beaulieu – 2,895 lbs

8th – Tancrède Archambault – 2,893 lbs

9th – Joseph Geoffrion – 2,837 lbs

10th – Joseph Vanier – 2,831 lbs

11th – William Leber – 2,777 lbs

12th – Pierre Gosselin – 2,777 lbs

13th – Léon Beaupré – 2,661 lbs

14th – Joseph Napoléon de la Durantaye – 2,658 lbs

15th – Avila Lavoie – 2,540 lbs

Arthur Dandurand finished in 16th place with a haul of 2,473 lbs

1st – Moïse Charbonneau – 3,246 lbs

2nd – Nazaire Belzil – 3,241 lbs

3rd – Joseph Allain – 2,951 lbs

4th – Alexandre Duchesne – 2,950 lbs

5th – Aquila Monette – 2,911 lbs

6th – Euclide Poulin – 2,899 lbs

7th – Pierre Beaulieu – 2,895 lbs

8th – Tancrède Archambault – 2,893 lbs

9th – Joseph Geoffrion – 2,837 lbs

10th – Joseph Vanier – 2,831 lbs

11th – William Leber – 2,777 lbs

12th – Pierre Gosselin – 2,777 lbs

13th – Léon Beaupré – 2,661 lbs

14th – Joseph Napoléon de la Durantaye – 2,658 lbs

15th – Avila Lavoie – 2,540 lbs

Arthur Dandurand finished in 16th place with a haul of 2,473 lbs

Moïse’s workplace was extremely proud of his achievement, and a party was organized in his honour. Congratulatory speeches were made and a special medal was awarded to him.

Though the contest was over, many people were not satisfied with the final results. While Mr. Charbonneau was expected to place, few expected him to win. And while his wheelbarrow was the heaviest, Mr. Belzil had pushed the wheelbarrow across the platform loaded with the same number of lead ingots. It was clear that others also had the ability to lift more than 3,000 lbs, but for a variety of reasons, did not during the contest. Plus, there were several supposedly very strong men who wanted desperately to enter the contest but missed the registration deadline. Some of these men issued challenges through La presse to the eventual winner of the contest.

To address these concerns, La presse decided to quickly organize a second wheelbarrow contest. It would be held the evening of March 18th, just two weeks after the conclusion of the first contest. Since it was believed that several men had the ability to exceed Mr. Charbonneau’s record, the minimum weight would be set at 3,250 lbs – four pounds heavier than the record. All competitors would have two chances to make a successful attempt at this weight, and those who succeeded would have another two attempts to cross the platform with the heaviest load that they could lift. Anyone was free to enter, but to limit the field to serious contenders, the registration fee was set at $10. There would be no cash prizes: it was felt that the honour of holding the world record would be sufficient motivation. (This said, there would also be medals for the top four finishers.)

To prepare for the contest, organizers secured a new wheelbarrow. The one used in the final round of the first contest wasn’t large enough to hold the number of lead ingots that were expected to be lifted. The same plans were used, with the only difference being the addition of a board near the front to allow a bigger load. An order for an extra 1000 lbs of lead was also placed.

It was hoped that the new contest would see Mr. Belzil, Mr. Charbonneau, Mr. Vanier, and some of the other new challengers take part. Nazaire was the first to register – he was very confident he could beat the record and desperately wanted a chance to prove it. He was even willing to bet on himself against the others. Moïse, on the other hand, was not interested in competing in the new contest. He felt that by winning the first contest, he didn’t have anything to prove. Instead, if a new record was set in the second contest, he said he’d return to try to take back the record. As for Mr. Vanier and some of the other new challengers, they simply never registered (some had apparently injured themselves in training).

In the end, only six men registered and showed up to compete on March 18th. All six had competed in the first contest: Nazaire Belzil, Alexandre Duchesne, Aquila Monette, Joseph Napoléon de la Durantaye, Arthur Dandurand, and Vital Bélair, who had finished 2nd, 4th, 5th, 14th, 16th, and 19th, respectively.

Once again, thousands of people attended Sohmer Park to see if Charbonneau’s record would be beaten, and who among the elite field would win the contest. At an opening weight of 3,250 lbs, it wouldn’t have been surprising if no one had managed to walk the required 25 feet. Not only did this happen, but five of the competitors went on to cross with more than 3,750 lbs – more than 500 lbs above the record set two weeks earlier! This significant increase was in large part due to the use of the new wheelbarrow, which allowed more weight to be loaded near the wheel and allowed for better balance.

So much weight was being lifted, that over the course of the evening there was a need for even more lead ingots! The extra 1,000 lbs that the organizers had secured for the contest wasn’t enough. Luckily, there was a foundry close by the venue and the owner was on hand to provide the additional lead required by the strongest competitors.

Arthur Dandurand had the best performance of the night, from a pound-for-pound perspective. His successful haul of 3,781 lbs represented more than 21 times his bodyweight! Another man who had a terrific showing was bricklayer Vital Bélair. At 50 years old, he was by far the oldest competitor of the group, yet he successfully pushed the wheelbarrow with almost 4,000 lbs loaded! But when all was done, one man had bested the others by a significant margin: Nazaire Belzil. His carry of 4,393 lbs surpassed Charbonneau’s record by 1,147 lbs!

Final standings of the March 18 wheelbarrow contest:

1st – Nazaire Belzil – 4,393 lbs

2nd – Aquila Monette – 4,081 lbs

3rd – Vital Bélair – 3,961 lbs

4th – Alexandre Duchesne – 3,841 lbs

5th – Arthur Dandurand – 3,781 lbs

1st – Nazaire Belzil – 4,393 lbs

2nd – Aquila Monette – 4,081 lbs

3rd – Vital Bélair – 3,961 lbs

4th – Alexandre Duchesne – 3,841 lbs

5th – Arthur Dandurand – 3,781 lbs

Nazaire’s dominant display successfully silenced his challengers. After March 18th, few doubters remained. Upon the publication of the results, many of Charbonneau’s supporters issued a letter of protest to La presse, saying that the record shouldn’t be counted, because the contest wasn’t run in the same manner as the first one. While the newspaper acknowledged the differences, their position was that Moïse could have competed in the contest. Had he competed, he would have had the same opportunity as the others to increase the record and to demonstrate his superiority with a wheelbarrow where the biggest limiting factor was the competitors’ strength.

La presse’s wheelbarrow contests from the winter of 1908 were a huge success. They captured the readership’s attention for several months, and new strength heroes emerged into the public eye. A new sport was created from a common work tool. In fact, standalone wheelbarrow contests continue to be held to this day in Quebec, and the wheelbarrow is still occasionally featured as an event in strongman contests. But in the past 111+ years, no wheelbarrow contest would match the level of excitement generated by the very first two….

Researched and Written by Eric Roussin